A new plesiosaur from the Lower Jurassic of Portugal and the early radiation of Plesiosauroidea

EDUARDO PUÉRTOLAS-PASCUAL, MIGUEL MARX, OCTÁVIO MATEUS, ANDRÉ SALEIRO, ALEXANDRA E. FERNANDES, JOÃO MARINHEIRO, CARLA TOMÁS, and SIMÃO MATEUS

Puértolas-Pascual, E., Marx, M., Mateus, O., Saleiro, A., Fernandes, A.E., Marinheiro, J., Tomás, C. and Mateus, S. 2021. A new plesiosaur from the Lower Jurassic of Portugal and the early radiation of Plesiosauroidea. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 66 (2): 369–388.

A new plesiosaur partial skeleton, comprising most of the trunk and including axial, limb, and girdle bones, was collected in the lower Sinemurian (Coimbra Formation) of Praia da Concha, near São Pedro de Moel in central west Portugal. The specimen represents a new genus and species, Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. Phylogenetic analysis places this taxon at the base of Plesiosauroidea. Its position is based on this exclusive combination of characters: presence of a straight preaxial margin of the radius; transverse processes of mid-dorsal vertebrae horizontally oriented; ilium with sub-circular cross section of the shaft and subequal anteroposterior expansion of the dorsal blade; straight proximal end of the humerus; and ventral surface of the humerus with an anteroposteriorly long shallow groove between the epipodial facets. In addition, the new taxon has the following autapomorphies: iliac blade with less expanded, rounded and convex anterior flank; highly developed ischial facet of the ilium; apex of the neural spine of the first pectoral vertebra inclined posterodorsally with a small rounded tip. This taxon represents the most complete and the oldest plesiosaur species in the Iberian Peninsula. It is also the most complete, best preserved, and oldest marine vertebrate in the region and testifies to the incursion of marine reptiles in the newly formed proto-Atlantic sea, prior to the Atlantic Ocean floor spreading in the Early Cretaceous.

Key words: Plesiosauria, radiation, Sinemurian, Jurassic, Iberian Peninsula, Europe.

Eduardo Puértolas-Pascual [eduardo.puertolas@gmail.com], GeoBioTec, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2829-516 Monte de Caparica, Portugal; Museu da Lourinhã, Rua João Luis de Moura, 95, 2530-158 Lourinhã, Portugal; Aragosaurus-IUCA Research group, Universidad de Zaragoza, Calle Pedro Cerbuna, 12, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain.

Miguel Marx [mpmarx1@gmail.com], Huffington Department of Earth Sciences, ISEM at Southern Methodist University, 75205 Dallas, Texas, USA; GeoBioTec, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2829-516 Monte de Caparica, Portugal; Museu da Lourinhã, Rua João Luis de Moura, 95, 2530-158 Lourinhã, Portugal.

Octávio Mateus [omateus@fct.unl.pt] and André Saleiro [andresaleiro@gmail.com], GeoBioTec, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2829-516 Monte de Caparica, Portugal; Museu da Lourinhã, Rua João Luis de Moura, 95, 2530-158 Lourinhã, Portugal.

Alexandra E. Fernandes [Ae.fernandes@campus.fct.unl.pt], SNSB-Bayerische Staatssammlung für Paläontologie und Geologie, Richard-Wagner-Str., 10, 80333 Munich, Germany; GeoBioTec, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2829-516 Monte de Caparica, Portugal; Museu da Lourinhã, Rua João Luis de Moura, 95, 2530-158 Lourinhã, Portugal.

João Marinheiro [joaomarinh@gmail.com], Parque dos Dinossauros da Lourinhã, Rua Vale dos Dinossauros, 25, 2530-059 Abelheira, Lourinhã, Portugal; Museu da Lourinhã, Rua João Luis de Moura, 95, 2530-158 Lourinhã, Portugal.

Carla Tomás [carla.alex.tomas@gmail.com], Museu da Lourinhã, Rua João Luis de Moura, 95, 2530-158 Lourinhã, Portugal.

Simão Mateus[simaomateus@gmail.com], Parque dos Dinossauros da Lourinhã, Rua Vale dos Dinossauros, 25, 2530-059 Abelheira, Lourinhã, Portugal; Museu da Lourinhã, Rua João Luis de Moura, 95, 2530-158 Lourinhã, Portugal; Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto, Via Panorâmica Edgar Cardoso, 4150-564 Porto, Portugal; GeoBioTec, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2829-516 Monte de Caparica, Portugal.

Received 11 September 2020, accepted 9 November 2020, available online 9 June 2021.

Copyright © 2021 E. Puértolas-Pascual et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (for details please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The earliest remains of unambiguous plesiosaurs are known from the Rhaetian (Wintrich et al. 2017a), with the early history of Plesiosauria being understood primarily from the Early Jurassic of Europe (e.g., De la Beche and Conybeare 1821; Conybeare 1824; Benson et al. 2012) and Greenland (Marzola et al. 2018). Except for a few occurrences (e.g., Sinemurian plesiosaurs from Australia; Kear 2012), the earliest Jurassic (Hettangian and Sinemurian) plesiosaur record is mostly restricted to England, with rhomaleosaurids such as Avalonnectes arturi Benson, Evans, and Druckenmiller, 2012, Eurycleidus arcuatus (Owen, 1840), Stratesaurus taylori Benson, Evans, and Druckenmiller, 2012, Macroplata tenuiceps Swinton, 1930, and Archaeonectrus rostratus (Owen, 1865), pliosaurids such as Thalassiodracon hawkinsii (Owen, 1840) and Attenborosaurus conybeari (Sollas, 1881) and plesiosauroids such as Eoplesiosaurus antiquior Benson, Evans, and Druckenmiller, 2012, Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus Conybeare, 1824, and Eretmosaurus rugosus (Owen, 1840) (Benson et al. 2012). While plesiosaur remains from the United Kingdom are known from well-represented specimens, the fossil record from the Iberian Peninsula remains scarce. Only fragmentary remains of plesiosaurians have been reported from Portugal and Spain (see Plesiosauria of the Iberian Peninsula table in SOM 1, Supplementary Online Material available at http://app.pan.pl/SOM/app66-PuertolasPascual_etal_SOM.pdf), with Jurassic plesiosaur material being particularly uncommon (Bardet et al. 2008a, b).

Geological setting

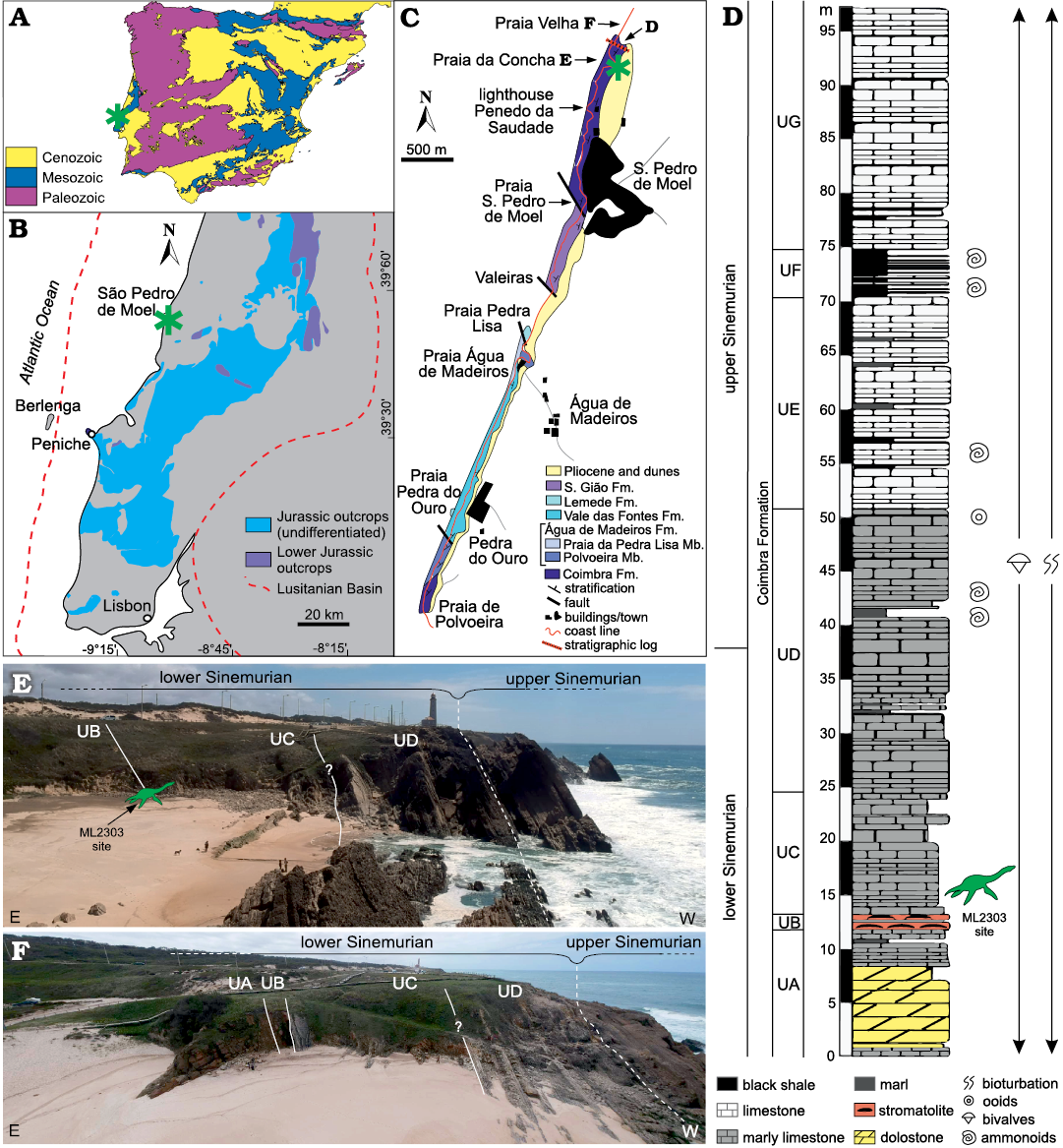

Specimen ML2302 was collected in Portugal, approximately 110 km north of Lisbon, in the municipality of Marinha Grande, near São Pedro de Moel, among the beach cliffs of Praia da Concha, north of the lighthouse Penedo da Saudade (Fig. 1). The specimen was found by Vitor Teixeira and António Silva (Porto, Portugal), who donated it to the Museu da Lourinhã in 2017. Praia da Concha contains outcrops of lower to upper Sinemurian deposits, of the Coimbra Formation (Duarte et al. 2008, 2014b), dated by numerous fossils such as ostracods (Cabral et al. 2013; Loureiro et al. 2013; Duarte et al. 2014a), brachiopods (Paredes et al. 2013b; Duarte et al. 2014a), bivalves (Paredes et al. 2013a; Duarte et al. 2014a) and ammonites (Duarte et al. 2008, 2014a).

Fig. 1. Geographical and geological settings of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. (ML2302) from the Lower Jurassic of São Pedro de Moel (Leiria, Portugal). Geological map of the Iberian Peninsula (A) and the Jurassic outcrops in the Lusitanian Basin (B) with study area indicated (asterisks). Geological mapping of the outcropping rock units in the São Pedro de Moel region (C) with location of the ML2302 site (asterisk). Synthetic stratigraphic column of the Coimbra Formation (D) recorded in the area of Praia Velha and Praia da Concha. Panoramic views of the outcrops and units of the Coimbra Formation in Praia da Concha (E) and Praia Velha (F). UA–UG, informal units of the Coimbra Formation. Modified from Duarte et al. (2008, 2014a, b).

The Coimbra Formation is part of the Lusitanian Basin, which is located on the western Iberian passive margin of the Atlantic, and provides an excellent marine record of the Early Jurassic. The Lusitanian Basin (Fig. 1B) is a north-south elongated basin, bordered by the Iberian Massif to the east and by the Variscan Berlenga Horst to the west (Fig. 1B). The development of this basin was favored by the opening of the Atlantic, and it has several rifting and sedimentary phases with deposits that span from the Upper Triassic to the Upper Cretaceous (e.g., Wilson et al. 1989; Alves et al. 2002; Duarte et al. 2014a, among others). The deposits studied in the present work were formed during the first phase, ranging from the Triassic to the Middle Jurassic, with the Lower Jurassic mainly composed by marine carbonate deposits (see Soares et al. 1993; Azerêdo et al. 2003; Duarte et al. 2004, 2014a).

The carbonate Jurassic deposits around São Pedro de Moel belong to the Coimbra Formation (early Sinemurian–late Sinemurian) and the overlying open-marine Água de Madeiros Formation (late Sinemurian). ML2302 was recovered in the lower part of the Coimbra Formation (Fig. 1D). This formation has been traditionally subdivided into two informal units, dolomite and limestone members (Azerêdo et al. 2003) or “Camadas de Coimbra” and “Calcários de S. Miguel” (Soares et al. 1985). In more recent and detailed sedimentological studies, the Coimbra Formation, in the section located between Praia Velha and Praia da Concha (Fig. 1C–F) (Praia da Concha-Farol section of Duarte et al. 2014b), has been divided into seven informal units (UA–UG) (Azerêdo et al. 2010; Duarte et al. 2014b). This section comprises a thick succession (almost 100 m) of dolostone, stromatolites, marlstone and bioclastic limestone with some marl/shales alternations (Fig. 1D–F).

ML2302 was recovered from a marlstone level located in the lower half of the Unit C (UC) of the Coimbra Formation (Fig. 1D, E). This unit has been dated as early Sinemurian as it is located several meters below the first appearance of the ammonites Ptycharietites and the Asteroceras obtusum Ammonite Zone located in the middle part of UD and marking the beginning of the upper Sinemurian (e.g., Duarte et al. 2008, 2014a, b; Azerêdo et al. 2010). Found interspersed throughout the matrix during preparation, surrounding the bones, were the internal molds of invertebrate mollusks, among which a few marine gastropods were able to be wholly removed and could be identified as Pseudomelania sp. commonly attributed to marginal-to-full marine environments (Schneider 2009). The depositional settings of the levels where ML2302 was found correspond to a transition from restricted marine environment, as evidenced by the occurrence of dolomitic facies (UA) and microbial facies with stromatolites (UB) located a few meters below the site of ML2302, to a gradual increase in fauna of marine macroinvertebrates (essentially bivalves and ammonites) in open-marine facies caused by a gradual rise of sea level (e.g., Duarte et al. 2008, 2014a, b; Azerêdo et al. 2010).

Institutional abbreviations.—FCT-UNL, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Caparica, Portugal; MG, Museu Geológico, Lisboa, Portugal; ML, Museu da Lourinhã, Lourinhã, Portugal.

Other abbreviations.—H, height; L, length; TBR, tree-bisection-reconnection; W, width.

Material and methods

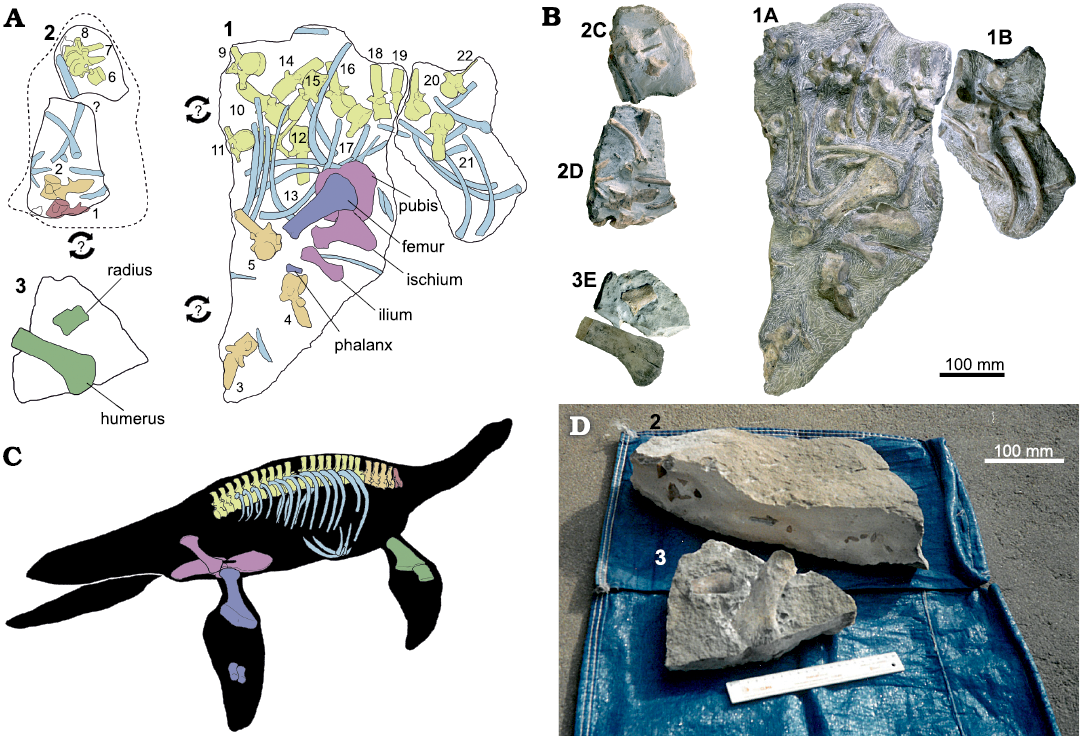

The material was originally discovered by António Silva, an amateur paleontologist, in the years 1999–2000, who also took some pictures of the material before preparation (Fig. 2D).

Blocks 1A and 1B (Fig. 2A, B) were extracted with a hammer and chisel from the site by Vitor Teixeira, a friend of António Silva, and in 2017 were donated to the Museum of Lourinhã.

In 2019, three additional blocks (2C, 2D and 3E; Fig. 2A, B), along with an isolated humerus, were donated to ML. Blocks 2C, 2D, and 3E were originally taken from the field in two separate pieces (block 2 and 3; Fig. 2D) but with some mechanical and experimental chemical preparation having been performed by the donors, the museum donation was made as three blocks and an isolated humerus. Although smaller, these blocks showed a more advanced state of preparation than 1A and 1B, bearing signs of matrix removal by the use of rotary tools, as well as marks caused by the use of acid solutions along the borders of the blocks in question.

Fig. 2. Bone mapping and reconstruction of the skeleton of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. (ML2302) from the Sinemurian (Lower Jurassic) of São Pedro de Moel (Leiria, Portugal). A. Bones distribution map of the three original extracted blocks (1, 2 and 3) containing ML2302. Arrows with question marks represent that the joining relationship between the blocks is unknown. B. Photographs of the five sub-blocks (1A, 1B, 2C, 2D, and 3E) after preparation works. C. Skeleton reconstruction with the preserved bones of ML2302. D. Archival photographs of how blocks 2 and 3 were found before their preparation. Drawings by SM.

Once ML received the blocks, the preparation process was begun by consolidating the exposed surfaces of bone with a 5% concentration of Paraloid B-72 in acetone. Once properly stabilized, the fossil was then transported to the DinoParque da Lourinhã, where preparation was continued using the following pneumatic tools: a Paleo Tools ME-9100 for the bulk removal of the surrounding matrix and a Paleo Tools Micro Jack 6 for more precise matrix removal. Throughout this process, all bone surfaces were consolidated with 5% Paraloid B-72 diluted in acetone, and any breaks or deep fissures were glued and reinforced with 20% or 50% Paraloid B-72 in acetone, as required.

Due to the brittle nature of the bones, when certain bones were deemed ready for extraction, any thinner features, such as pelvic bones and vertebrae neural spines were temporarily reinforced by facing the bone surfaces with surgical compresses cut to size, and soaked in 5% Paraloid B-72 in acetone. Further temporary structural stabilization was sometimes provided by using bamboo skewers, also cut to size, as a splint in between the compress layers. Due to the opacity of the compresses hindering view of the bone surfaces for study, these stabilization methods were eventually removed by dissolving the adhesive with acetone, and then replaced with Tengujo Japanese paper, 6 g/m2, soaked in 5% Paraloid B-72 in acetone, chosen for its strength and more transparent properties.

The bones that were selected for removal from the original blocks were those that were deemed most stable and necessary for anatomical and taxonomic studies. Remaining bones were left in situ, not only for stability and eventual exhibition purposes, but primarily for the preservation of taphonomical information.

Keeping in mind the importance of this particular specimen, and that the locality from which the specimen came from has been known to also produce pyritized fossils, further studies are being developed which will focus on its preventive conservation.

The specimen is to be housed in accordance with current archival standards, and the entire preparation process was extensively recorded with written documentation and accompanying photographs.

Measurements.—Length, width, and height indices of the centra were measured where possible on exposed centra, in addition to the width of the transverse processes, and height of the neural spines and neural arches (see SOM 2: table 1). Length, breadth, and height of the exposed centra were measured according to the standardized methods of Welles (1952), Brown (1981), and Smith and Araújo (2017). Welles (1952) defines breadth (width) as being measured across the anterior articular facet of the centrum. Brown (1981) utilizes the posterior articular facet for determining width. Smith and Araújo (2017) standardize the anterior articular facet as the articular end of the centrum from which to derive width. Length is defined in Welles (1952) as the distance between the anterior articular facet and the posterior articular facet, while Brown (1981) and Smith and Araújo (2017) specifically define length as being measured along the ventral margin of the centrum. The height of the centrum is defined along the anterior articular facet in Welles (1952), and Smith and Araújo (2017), while Brown (1981) defines the height along the posterior articular facet. Centrum dimensions were measured using all three methods in order to recover as much dimensional data from the centra as possible.

Systematic palaeontology

Sauropterygia Owen, 1860

Plesiosauria de Blainville, 1835

?Plesiosauroidea Gray, 1825 (sensu Welles 1943)

Genus Plesiopharos nov.

Type species: Plesiopharos moelensis sp. nov., see below; monotypic.

Etymology: From the Ancient Greek πλησίον [plēsíon], close, near; prefix alludes the plesiosaurian affinity, and pharos, [φάρος], lighthouse, referring to the nearby lighthouse where the specimen was discovered.

Diagnosis.— As for the monotypic type species.

Plesiopharos moelensis sp. nov.

Etymology: After São Pedro de Moel, the nearest locality.

Holotype: ML2302 is a partial skeleton belonging to a single individual that consists of 22 vertebrae (one cervical, four pectorals, and 17 dorsal vertebrae), one cervical rib and at least 19 dorsal ribs, two gastralia, right humerus, radius, ischium, ilium, pubis, femur, and two phalanges.

Type locality: Praia da Concha, north of São Pedro de Moel, municipality of Marinha Grande, district of Leiria, region Centro, Portugal. Coordinates: 39°46’03.9” N, 9°01’44.8” W.

Type horizon: Coimbra Formation, lower Sinemurian (Early Jurassic).

Diagnosis.—Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. is a plesiosaur diagnosed by the following autapomorphies: iliac blade with rounded and convex anterior flank and less expanded than the posterior flank; ischial facet of the ilium highly developed and twice as long as the acetabular facet; first pectoral vertebra with the apex of the neural spine inclined posterodorsally and forming a small rounded tip at the posterodorsal margin. For the exclusive combination of synapomorphies see phylogenetic analysis section.

Description.—General preservation: Most of the elements are preserved in semi-articulation, namely, the bones are almost in contact with each other and approximately in their anatomical position, although most of them are not articulated since there is a slight post-mortem displacement. Most bones are well preserved, with no signs of deformation or crushing, preserving their three-dimensionality.

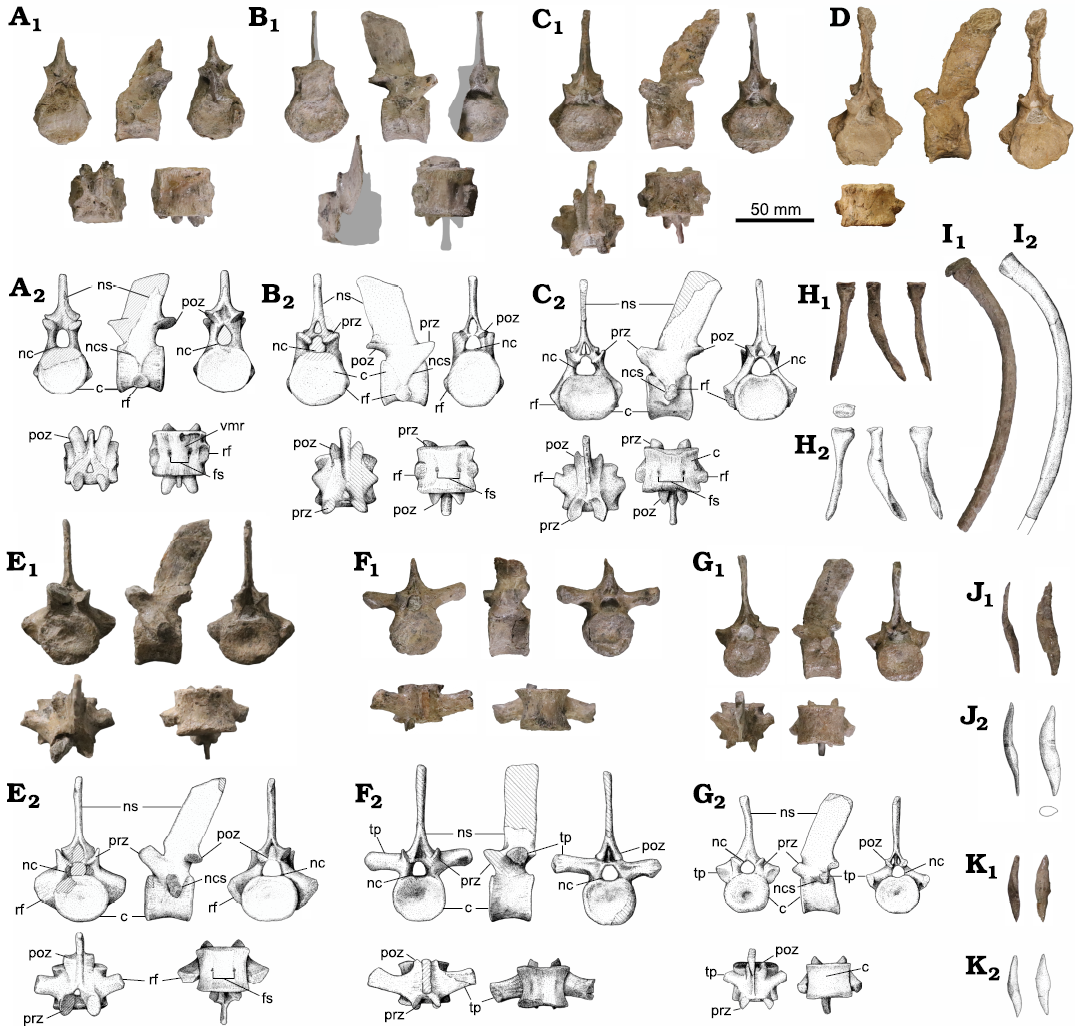

Vertebrae: A total of 22 vertebrae are associated with ML2302. The majority of the vertebrae are mostly well-preserved, although some breakage has affected the preservation in several vertebrae. The one preserved cervical vertebra is visibly eroded, missing the prezygapophyses and most of the neural spine. One dorsal vertebra is missing most of its neural spine, and a second dorsal vertebra completely lacks its neural spine, which has weathered away. Overall, the distal margins of the neural spines and transverse processes appear to have suffered the most damage in ML2302. The preserved vertebrae include one cervical, four pectoral, and seventeen dorsal vertebrae, with the last “dorsal” vertebra possibly being the first sacral. The location of the vertebrae within the vertebral column was determined by the location of the rib facet on the centrum, the morphology of the rib facet, the location of neurocentral suture relative to the rib facet, and the preserved semi-articulation of the vertebral column in ML2302 (Brown 1981; Sachs et al. 2013). Six vertebrae have been completely removed during preparation from the rock matrix (Fig. 3), while the rest remain in four blocks (Fig. 2). The largest block contains eleven well-preserved dorsal and three pectoral vertebrae, and more than a dozen ribs and rib fragments (block 1A; Fig. 2). One of the recovered blocks connects directly with the large block and contains three posterior dorsal vertebrae and at least nine dorsal ribs and rib fragments (block 1B; Fig. 2). A third block includes three anterior dorsal vertebrae along with the fragment of a fourth vertebra (block 2C; Fig. 2). The last block includes a cervical and a pectoral vertebra (block 2D; Fig. 2).

All observable vertebrae are sub-platycoelous with a slight depression located in the center of the articular facets. Nearly all the centra are slightly excavated along the dorsal margin by the neural canal. The neural arches are all fully fused to the centra. The combined width of the prezygapophyses is slightly narrower than the centrum in all observable vertebrae of ML2302. The prezygapophyses of all observable vertebrae extend beyond the anterior articular facet of the centra, and the postzygapophyses extend to approximately the level of the posterior articular facet of the centrum or further posteriorly. The postzygapophyses of all the vertebrae are thickest at the articular facet and are oriented ventrolaterally.

One vertebra has been identified as a cervical vertebra (Fig. 3A), as it lacks transverse processes, exhibits rib facets on the ventrolateral surface of the centrum, and lacks contact between the neurocentral suture and the rib facets. This cervical vertebra most likely corresponds to the posterior-most position of the cervical column, as the centrum exhibits length, width, and height dimensions that are sub-equal to centrum dimensions in the pectoral vertebrae, and was also located in situ anterior to the first pectoral vertebra. The centrum of this cervical vertebra is wider than it is long and high, whereas the length is subequal to the height (W > L, H; L ≈ H). The anterior articular facet of the cervical centrum is damaged, however the posterior articular facet is preserved and presents a subcircular outline. The cervical vertebra exhibits two co-joined facets (diapophyses fused with parapophyses) to receive the heads of the cervical ribs. The rib facets protrude ventrolaterally in the cervical centrum. In lateral view, the ventral surface of the cervical centrum is slightly concave, and the neurocentral suture makes a high relief v-shape. Below the ventral-most extent of the neurocentral suture in the cervical vertebra is a low ridge that extends to the dorsal margin of the rib facet. The neural arch is sutured to the centrum of the cervical vertebra, so the specimen was apparently adult (Vaughn 1955; Brown 1981; O’Keefe 2004b). Nevertheless, the neurocentral suture is still visible, so the specimen may be a young adult (Storrs 1997; O’Keefe 2004b). In ventral view, the centrum is slightly hourglass shaped, and the median ventral surface of the centrum is slightly rounded and convex rather than having a sharp crest or a flat surface. Ellipsoidal foramina subcentralia straddle the median ventral ridge in the cervical centrum.

Fig. 3. Axial bones of the plesisaur Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. (ML2302) from the Sinemurian (Lower Jurassic) of São Pedro de Moel (Leiria, Portugal). A. Last cervical vertebra (Fig. 2A: 1). B. First pectoral vertebra (Fig. 2A: 2). C. Second pectoral vertebra (Fig. 2A: 3). D. Third pectoral vertebra (Fig. 2A: 4). E. Fourth pectoral vertebra (Fig. 2A: 5). F. Dorsal vertebra (Fig. 2A: 9). G. Last dorsal vertebra (Fig. 2A: 22). In anterior, lateral, posterior, dorsal, and ventral views, respectively. H. Anterior or posterior dorsal rib in proximal (in H2), dorsal, anteroposterior, and ventral views, respectively. I. Middle dorsal rib in anteroposterior view. J, K. Lateral gastralia in anteroposterior and dorsoventral views, and cross section (in J2), respectively. Photographs (A1–C1, D, E1–K1) and explanatory drawings (A2–C2, E2–K2); drawings by SM. Abbreviations: c, centrum; fs, foramina subcentralia; nc, neural canal; ncs, neurocentral suture; ns, neural spine; poz, postzygapophyses; prz, prezygapophyses; rf, rib facet; tp, transverse process; vmr, ventromedial ridge.

Four vertebrae of ML2302 have been identified as pectoral vertebrae (Fig. 3B–E) based on a dorsoventrally deep rib facet transected or contacted by a v-shaped neurocentral suture (Seeley 1874; Brown 1981; Evans 2012; Sachs et al. 2013). The anterior-most pectoral vertebra was located in situ directly posterior to the last cervical vertebra (Fig. 2A, B), and is identified as a pectoral vertebra based on the contact between the neurocentral suture and the dorsal margin of the rib facet (Evans 2012). The first pectoral vertebra (Fig. 3B) exhibits rib facets on the ventrolateral surface of the centrum that are single-headed. The rib facets of the anterior-most pectoral vertebra are also oriented slightly more laterally than the last cervical vertebra. In ventral view of the first pectoral vertebra, the median ventral convexity is less pronounced than that of the posterior cervical vertebra. The other centra of ML2302 exhibit a ventral surface without a median convexity. The neural spine of the first pectoral vertebra is completely preserved and is dorsoventrally shorter and anteroposteriorly longer than the neural spines of the other pectorals and dorsal vertebrae. The neural spine rises with a posterior inclination above the neural arch. In lateral view, the spine is 1.5 times higher dorsoventrally and almost as long anteroposteriorly as the centrum (SOM 2: table S1). The anterior and posterior margins of the first pectoral vertebra neural spine are straight and parallel to each other. The apex of the spine is inclined anteroventrally, with the posterior margin of the spine forming a rounded tip which is taller than the anterior margin. In anteroposterior view, the articular surfaces of the zygapophyses in the pectoral vertebrae, as in all the preserved vertebrae, are medioventrally inclined, and the distance between each pair of zygapophyses is slightly smaller than the width of the centrum, although they do not touch each other medially. Regarding pectoral vertebrae 2–4 (Fig. 3C–E), the rib facets are dorsoventrally deep, and situated below the neural canal. Both the pre- and postzygapophyses extend beyond the articular facets of the centra. In ventral view of the pectoral vertebrae, paired foramina subcentralia are evident and are not as widely separated as in the middle dorsal vertebrae. In lateral view, the neural spines of the pectoral vertebrae are posteriorly inclined. One of the mid-pectoral vertebrae (Fig. 3C) exhibits a damaged neural spine, while the neural spine from the mid-pectoral vertebra 3 (Fig. 3D) is better preserved, and exhibits a neural spine with a slightly convex anterior margin and a sub-straight posterior margin, thus, creating a nearly “shark-fin” shape. The last pectoral vertebra (Fig. 3E) exhibits a posteriorly inclined neural spine with straight and parallel anterior and posterior margins. In the last pectoral vertebra, the neurocentral suture makes light contact with the rib facet along the ventral margin.

The dorsal vertebrae of ML2302 (Fig. 3F) exhibit fully formed diapophyses with transverse processes that extend nearly straight horizontally from the neural arch, although the transverse processes of the posterior dorsal vertebrae are shorter than those of the anterior and middle dorsal vertebrae and are oriented ventrolaterally. Approximately 17 dorsal vertebrae are preserved in ML2302. The transverse processes of the anterior and middle dorsal vertebrae are dorsoventrally compressed with an ovate cross-section, and extend laterally beyond the body of the centra. The first two dorsal vertebrae exhibit tuberosities below the transverse processes on the lateral surface of the centra that are likely remnants of the parapophyses, as the preceding vertebrae are from the pectoral region (Evans 2012). The diapophyses of the anterior and mid-dorsal vertebrae exhibit a swelling where the head of the dorsal ribs would have attached. In dorsoventral view, the transverse processes are oriented slightly posterolaterally. The lateral surfaces of the mid-dorsal centra bodies are noticeably constricted between the anterior and posterior articular facets. The neural spines of the mid-dorsal vertebrae rise straight above the neural arch and are not posteriorly inclined, while the anterior dorsal neural spines exhibit a slight posterior inclination. In lateral view of the dorsal vertebrae, the anterior and posterior margins of the neural spines are straight and parallel to each other. The apex of the dorsal neural spines is slightly convex in lateral view. The neural spine of each dorsal vertebra is taller than its respective centrum and is transversely compressed. The prezygapophyses are oriented anterodorsally and slightly medially. Articular facets of the prezygapophyses form concave depressions that face dorsomedially.

The two posterior-most dorsal vertebrae (Fig. 3G) indicate a transition to the pelvic region of ML2302. In these posterior dorsal vertebrae, the transverse processes are more ventral than in the other dorsal vertebrae and are partially involved in the vertebral centrum but are situated above the neurocentral suture. The transverse processes in the posterior dorsal vertebrae are more gracile and cylindrical in shape than the anterior and mid-dorsal vertebrae, and are oriented ventrolaterally. The diapophyses present a flat articular surface. The transverse processes are located immediately above the neurocentral sutures, which make a u-shape in lateral view. The centra of the posterior dorsal vertebrae, between the anterior and posterior articular facets, are slightly constricted, although less so than the mid-dorsal centra. The dimensions of the centra and neural spines of the posterior dorsal vertebrae are smaller than that of the anterior and mid-dorsal vertebrae. A single unpaired foramen is visible on the right ventrolateral surface of the posterior-most dorsal centra. Another foramen is visible on the left ventrolateral surface of the posterior dorsal centrum remaining in the unprepared block, although the right lateral surface of this vertebra is obscured by the rock matrix. In lateral view, the anterior and posterior margins of the neural spines are straight, parallel and slightly inclined posteriorly. It should be noted that the last dorsal vertebra (Fig. 3G) could be the first sacral vertebra. While the neurocentral suture appears below the facet for the rib, the facet overlies the dorsolateral surface of the centrum and is located below the neural canal. Without an associated dorsal or sacral rib, it cannot be known if the last dorsal is indeed a dorsal or the first sacral. However, the arrangement of the neurocentral suture below the transverse processes would indicate that it is probably the last dorsal.

Ribs and gastralia: One putative cervical rib, about 19 dorsal ribs, and two gastralia have been recovered. Most of the cervical rib is obscured by matrix and partially broken, preventing a detailed description. Only a flat rib facet and a pointed fragment that could correspond to one of the processes can be observed.

Most of the ribs are from the dorsal series (Fig. 3H, I), as determined by their elongated morphology and size relative to the associated vertebrae. The ribs are kinked at the neck and are compressed mediolaterally along the length of the body. The facets of the ribs in ML2302 are either flat to slightly concave with a circular cross-section, or slightly compressed anteroposteriorly. Distally, the ribs transition to an ovate cross-section, becoming more mediolaterally compressed. There is a smooth and subtle constriction distal to the head of the ribs on the surface of the neck. Subtle parallel ridges run along the proximal margin of the ribs.

Only two gastralia elements (Fig. 3K, J) are associated with ML2302. The gastralia are dorsoventrally compressed and spool-shaped, with distal ends that taper. The larger element is distinctly sigmoidal. Due to its asymmetric sigmoidal morphology, both gastralia probably correspond to the lateral gastral ossicles, which are different from the bilaterally-symmetrical midline ossicles.

Forelimb: humerus: The right humerus has been completely preserved (Fig. 4B), although it has some fractures and the proximal joint facet is slightly eroded. The humerus is a flat, robust, paddle-shaped bone, as long as the femur and slightly bent posteriorly. The proximodistal length, from the articular head to the distal end, is 150 mm, and the maximum anteroposterior width of the humerus, located in the distal region, is 72 mm. Consequently, its maximum proximodistal length is about twice its maximum anteroposterior width. The maximum anteroposterior width at the proximal end is 40 mm. The maximum dorsoventral height occurs at the proximal articular head and is about 40 mm. This thickness is influenced by the dorsal expansion of the tuberosity of the humerus. The minimum dorsoventral height of the humerus is 15 mm, and it occurs approximately at the midlength of the bone. The maximum dorsoventral height in the distal region is 20 mm. For the complete list of measurements see SOM 2: table S2.

In dorsoventral view, the humerus is slightly asymmetrical with a postaxial expansion in the distal region that makes the posterior (postaxial) outline concave while the anterior (preaxial) border remains straight without any preaxial expansion, a primitive character found in Liassic plesiosaurs (Storrs 1997; Bardet et al. 1999b; O’Keefe 2001). This asymmetry differs from the morphology observed in the femur, which is almost symmetric with equal anteroposterior expansions in the distal region. The postaxial expansion of the distal region begins at approximately half of the total length of the humerus, orienting the articular facet of the ulna posterolaterally, while the facet of the radius lies along the axis of the humerus shaft and is oriented more laterally. The angle between both articular facets is approximately 120°. With the exception of the postaxial expansion, the anterior and posterior margins of the shaft are straight and parallel, maintaining a constant anteroposterior width of about 4 cm along the rest of the shaft. Consequently, there is also no distinctive postaxial process, only a smooth convexity in the postaxial margin near the proximal articulation. In dorsal view, the articular distal margin of the humerus is curved and convex, without any marked inflexion point between the facets for the radius and ulna. However, in ventral view, the facet of the radius is straighter while the facet of the ulna is markedly convex, therefore they can be slightly differentiable.

In distal view, the distal articular margin is groove-shaped for the ulna and the radius insertion, and although there is a small step that marks the boundary between these two articular facets, there is no observable extra facet for accessory ossicles. The presence of a groove-shaped insertion surface for the radius and the ulna could indicate maturity in the specimen. With the exception of the fine longitudinal striations running along the humerus, no grooves or crests are observed on the dorsal, ventral, anterior or posterior surfaces of the humerus. In ventral view, rather than a groove, there is a proximodistally short and anteroposteriorly long shallow depression between the two epipodial facets. A series of slightly more pronounced longitudinal rugosities are present around the first quarter of the proximal region of the shaft, and more abundant in the ventral region. In anteroposterior view, the proximal region of the shaft is dorsally expanded, while the ventral region remains almost straight along the entire body of the humerus. This expansion begins approximately in the middle region of the shaft and gradually increases proximally, producing the slightly concave dorsal contour of the humerus. This elevated surface on the proximal articular region coincides with the presence of the tuberosity of the humerus, however, the proximal articular face is slightly eroded. Thus, it is difficult to make inferences about this structure, or others such as the capitulum. Despite this erosion, in proximal view, an ovoidal cross-section of the proximal articulation can be inferred, and is slightly wider in the ventral facet (where the capitulum is located) and somewhat narrower in the dorsal area, where the humeral tuberosity is placed.

Radius: Only one epipodial bone has been preserved and has been identified as the right radius (Fig. 4C). As the specimen was not fully articulated, we cannot completely rule out that this bone is a tibia, since the tibia and the radius are usually very similar in shape and dimension. However, several reasons support its identification as a radius: although not in its exact anatomical position, the bone was found in situ next to the humerus (Fig. 2D); the bone fits and articulates perfectly with the radial facet of the humerus; and, usually, tibiae are somewhat more robust and anteroposteriorly wider with the distal and proximal margins having a similar anteroposterior development. With the exception of a small break notching into the preaxial margin, the bone is complete and well preserved. The radius is a flat, robust bone with a straight preaxial margin and concave postaxial border. It is longer than it is wide, with a maximum proximodistal length of 50 mm and a maximum anteroposterior width of 37 mm in the proximal area that articulates with the humerus. The distal margin that articulates with the radiale and the intermedium is narrower with an anteroposterior width of 26 mm. The bone is also quite flat, with a maximum dorsoventral height of 12 mm in the proximal and distal regions. In anteroposterior view, the cross-section of the radius has a slight hourglass shape, with a minimum dorsoventral height of 7 mm in the center and greater expansions, as mentioned, in the articular regions. For the complete list of measurements see SOM 2: table S2.

Both proximal and distal articulation facets are mostly concave in dorsoventral view. The anteroproximal and anterodistal corners of the radius are rounded without any prominent anterior flange. In dorsoventral view, there is a posterior expansion in the posteroproximal region of the radius that produces a concave postaxial margin. As a consequence of this concave margin, the presence of a proximodistally elliptic epipodial foramen between the radius and ulna can be inferred. Because the postaxial margin does not have an extremely marked concavity, the epipodial foramen would be slightly shorter than the epipodials. In proximal view, the outline of the articulation facet with the humerus is elliptical and anteroposteriorly elongated, with a flatter ventral margin and a wedged anterior margin. In distal view, the outline of the distal articulation facet is anteroposteriorly shorter than the proximal and it is ovoidal.

Pelvic girdle: All the bones from the right half of the pelvic girdle (Fig. 4H), including the right pubis (Fig. 4F), ilium (Fig. 4G), and ischium (Fig. 4E), have been preserved with little breakage or erosion. The surface of the bones is slightly striated. The general shape and dimensions of the pelvic girdle are here calculated by making a mirror image of the right side to establish bilateral symmetry. Therefore, the union of both pubes and ischia creates a heart-shaped contour in dorsoventral view. The total width of the complete pelvis has been estimated at 184 mm (distance between the lateral margins) and the total anteroposterior length is 188 mm (distance between the anterior-most margin of the pubis and the posterior tip of the medial blade of the ischium). The pelvic fenestration (also called puboischiatic fenestra by Dalla Vecchia (2017), Storrs (1997); or thyroid fenestra by Evans (2012) is elliptical and wider lateromedially (40 mm) than anteroposteriorly long (34 mm). All the articular surfaces of the pelvic girdle are slightly concave, well defined, pitted and irregular, indicating the presence of cartilage in life. While the lateral articulation between the pubis and the ischium is mediolaterally thick, its contact medial to the pelvic fenestra is thinner but seems to be present. Consequently, the pelvic bar would be complete. The laterally directed edges of the medial symphysis of the pubis, the posteromedial process of the pubis, and the anteromedial process of the ischium indicate that an anteroposteriorly elongated rhombic gap was located in the center of the pelvic bar.

Fig. 4. Limb bones and pelvic girdle of the plesiosaur Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. (ML2302) from the Sinemurian (Lower Jurassic) of São Pedro de Moel (Leiria, Portugal). Right femur (A), humerus (B), and radius (C), in proximal, dorsal, anterior, ventral, posterior, and distal views, respectively. D. Phalanx in dorsal, anteroporterior, and ventral views, respectively. Right ischium (E) and pubis (F), in ventral and dorsal views, respectively. G. Right ilium in distal, proximal, dorsal, posterior, ventral, and anterior views, respectively. The dashed lines in G2 highlight the curvature of the iliac blade. Photographs (A1–G1) and explanatory drawings (A2–G2). H. Anatomical reconstruction of the right side and mirrored left side of the pelvic girdle in dorsal view. Drawings by SM. Abbreviations: ace, acetabulum; adr, adductor rugosity; apis, anteromedial process of the ischium; cap, capitulum; cor, anterolateral cornu; epf, epipodial foramen; fif, fibular facet; gr, groove; huf, humeral facet; il, ilium; ilbl, iliac blade; ilf, iliac articular facet; ilsh, iliac shaft; is, ischium; isf, ischial articular facet; issh, ischial shaft; is sym, ischial symphysis; mebl, medial blade of the ischium; no, notch; pb, pelvic bar; pppu, posteromedial process of the pubis; pu, pubis; puf, pubic articular facet; pu sym, pubic symphysis; pvf, pelvic fenestra; raf, radial facet; radf, radiale facet; rug, rugosity; tif, tibial facet; tr, trochanter; trc, trochanteric crest; tub, tuberosity; ulf, ulnar facet.

Pubis: The right pubis (Fig. 4F) is a nearly complete flat plate of bone, having lost only a small fragment of the anterolateral margin, which still remains embedded in the rock matrix. The pubis is approximately as long anteroposteriorly as it is wide mediolaterally. It is a maximum of 94 mm in anteroposterior length (from the anterior-most margin to the posterior ischial facet), 92 mm in maximum mediolateral width (the distance between the medial and lateral margins without counting the anterolateral cornu), and about 8 mm in dorsoventral height (measured from the central region of the pubis). In lateromedial view, the cross-section of the pubis is flatter on the ventral surface and more convex on the dorsal surface. Both dorsal and ventral surfaces are covered by faint radial striations which are more apparent closer to the margins. For the complete list of measurements see SOM 2: table S3.

In dorsoventral view, the outline of the pubis, without counting the posterior concavity of the pelvic fenestra, exhibits a roughly hexagonal shape. The contour of the anterior half of the pubis consists of two distinct anteriorly convex margins divided by a notch. This notch is located on the anterolateral margin of the pubis, thus the medial anterior convexity is larger and more anteriorly placed than the lateral one. The presence of an anterior notch generally indicates greater ontogenetic development of the individual in contrast to the semi-lunate and rounded pubes observed in juvenile plesiosaurs (Welles 1943; Brown 1981; Bardet et al. 2008a). The anterolateral edge seems rounded, although it is also slightly damaged and a small portion of bone remains in the rock matrix. However, the damaged part is minimal, so it can be inferred that the anterolateral cornu of the pubis was rounded and poorly developed. In dorsoventral view, the lateral margin of the pubis is straight and anteroposteriorly aligned. Posterior to this lateral margin is the acetabular articulation, which slightly faces lateroposteriorly. The angle between the lateral edge and the acetabular margin is about 155°, and the angle between the acetabular margin and the articular ischial facet is about 120°. In lateral view, the lateral edge is very thin dorsoventrally until it significantly expands, coinciding with the acetabular facet of the pubis, which is triangular in outline and tapered anteriorly. In dorsoventral view, the medial margin of the pubis is straight and faces medioposteriorly. Most of the medial edge corresponds with the pubic symphysis and the posterior-most end corresponds with the posteromedial process of the pubis, which is curved posterolaterally and pointied posteromedially. In medial view, the pubic symphysis is flat, rugose, lenticular in cross-section and tapered posteriorly until it reaches the posteromedial process of the pubis. This lenticular cross-section has its maximum convexity along the dorsal surface, while the ventral surface is almost straight. In dorsoventral view, the posterior edge of the pubis is strongly concave, forming a deep semi-circular notch that corresponds with the anterior margin of the pelvic foramen. The articular ischial facet of the pubis is straight and faces posteriorly, and is located lateral to the pelvic foramen. The pubis lacks any kind of articulation with the ilium. The posteromedial process of the pubis is located medial to the pelvic foramen. This process is thinner and more rounded than the articular ischial facet, and is laterally curved and tapered, with the tip pointing in a posterolateral direction. In posterior view, the margin of the pelvic foramen and the posteromedial process of the pubis are very thin dorsoventrally, while the articular ischial facet is dorsoventrally expanded with an elliptical cross-section.

Ischium: The right ischium is seemingly complete (Fig. 4E), although for reasons of maintaining fossil stability, the ventral surface remains unprepared. In dorsoventral view, the ischium presents the typical hatchet-shaped outline present in plesiosaurians. Most of the ischial body, with the exception of the articular head, is dorsoventrally flat and plate-like. It has a very similar anteroposterior length and lateromedial width to the pubis, but it is slightly anteroposteriorly shorter. Therefore, the ischium is short, approximately as long as it is wide, with a total length of 90 mm (from the tip of the anteromedial process to the posterior tip of the medial blade) and a width of 83 mm (from the medial edge to the lateral margin of the iliac articular head). For the complete list of measurements see SOM 2: table S3.

As a consequence of the pelvic fenestration, the anterior margin of the ischium is deeply concave and semi-circular. This anteriorly concave edge has the same shape and dimension as the complementary concavity observed on the posterior margin of the pubis. The articular head of the ischium is massive (maximum length⁄width is 39⁄23 mm) and is located lateral to the pelvic fenestra. In dorsoventral view, the articular head is laterally convex, semi-circular and bears three articular facets. In lateral view, the articular surface, including the three facets, is rough and elliptical in cross-section. The anterior facet corresponds to the articulation with the pubis. In dorsoventral view, this facet is mediolaterally wide and straight, and in anterior view is dorsoventrally thick with a triangular outline that tapers medially. Posteriorly, forming an angle of 130° with the pubic articular facet, is a lateral facet that corresponds to the acetabulum and the articulation with the femur. This lateral facet has a subcircular outline and is bigger and dorsoventrally thicker than the other two facets. The posterior-most facet of the ischial head corresponds with the iliac articulation facet. This articulation has a triangular outline that tapers posteromedially, is longer than the two anterior facets, and faces posterolaterally.

The articular head of the ischium transitions to the rest of the ischium via a constriction, which forms a lateromedially-directed shaft or neck. The shaft is relatively slender, lenticular in cross-section, and has an anteroposterior length of 24 mm and a dorsoventral height of 8 mm at its narrowest section. Medially, this shaft expands anteroposteriorly to form the anteromedial process of the ischium and the medial ischial blade. The posterior expansion is the longest and widest and corresponds to the medial ischial blade. The lateral margin of this blade is oriented posteromedially, while the medial margin, where the ischial symphysis is located, is straight anteroposteriorly. A portion of the medial margin has a flat and rough articular surface, indicating the presence of cartilage in the symphyseal region for attachment of the left ischium. The ischial symphysis and the anterior margin of the ischial neck form an angle of 90°. The posterior margin of the blade is lateromedially wide and rounded. In contrast, the anteromedial expansion of the ischium begins medial to the pelvic foramen, is anteroposteriorly shorter, lateromedially narrower and tapers gradually to a thinner, rounded tip. This anteromedial process corresponds to the connection with the pubis to form a complete pelvic bar.

Ilium: The right ilium is complete (Fig. 4G), with almost no signs of erosion. Only a small portion of the anterior and posterior margins of the iliac blade are partially worn (although not significantly), which does not affect the general shape. The ilium is an elongated bone with anteroposteriorly expanded proximal and distal ends. When it is in articulation with the ischium, the ilium is directed posterodorsally. The total proximodistal length of the ilium, from the acetabular facet to the distal end of the iliac blade, is 78 mm. The maximum anteroposterior expansion of the proximal region, from the anterior margin of the acetabular facet to the posterior margin of the ischial facet, is 34 mm, with a maximum proximodistal length of 17 mm. The lateromedial height of the shaft is 12 mm and its maximum anteroposterior width is 13 mm, giving the shaft a subcircular cross-section. The maximum anteroposterior expansion of the iliac blade is 25 mm. The iliac blade is transversally compressed with a lateromedial width of 8 mm. For the complete list of measurements see SOM 2: table S3.

The proximal end of the ilium is the thickest region of the bone and bears a posteroventral ischial facet and a ventral facet for the acetabulum. The surface of the ischial facet is flat and rough, and the acetabular facet, although partially covered by matrix, seems to be concave. In proximal view, both facets together have a teardrop-shaped outline, with the acetabular facet lateromedially thicker than the ischial facet, a flat lateral margin, and a medial margin more convex and rounded. The ischial facet is almost twice as long anteroposteriorly (30 mm) than the acetabulum facet (17 mm), and the angle formed by both articular facets is about 100°. The pelvic or proximal articular end is expanded anteriorly and posteriorly. While the posterior expansion is directly related with the extension of the ischial facet, the anterior expansion is related to the participation of both the ischial facet and the acetabular facet. As a consequence of the latter, the anterior expansion is slightly larger. The shaft of the ilium is relatively straight and smooth, without any ridges, tubercles, or knees. The anteroposterior expansion of the iliac blade is restricted to the dorsal one-third of ilium. Although these anterior and posterior expansions can be considered sub-equal, the posterior expansion is slightly larger. In lateromedial view, the outline of the posterior expansion is concave, the anterior expansion is more rounded and convex, and the dorsal/distal margin is rounded and convex. This anteroposterior expansion is approximately double the minimum width of the shaft. In distal view, the iliac blade has a lenticular cross-section. The expansions of the iliac blade and the proximal articular end are not oriented in the same plane, and are rotated about 45° from each other. Both lateral and medial faces of the iliac blade are flat, without any signs of a facet for a sacral rib. A series of very fine proximodistal striations can be observed on both the iliac blade and the proximal end.

Hindlimb: femur: Only the right femur is preserved (Fig. 4A), but it is complete and exhibits very little signs of erosion. The femur is a straight, long, and paddle-shaped bone with expanded proximal and distal ends. Its maximum proximodistal length (130 mm) is twice its maximum anteroposterior width (65 mm). The maximum dorsoventral height occurs at the proximal articular head and is about 37 mm. This thickness is influenced by the dorsal expansion of the trochanter and the ventral expansion of the capitulum. The maximum anteroposterior width at the proximal end is 34 mm. From the maximum proximal expansion, the shaft progressively constricts distally, until reaching an anteroposterior width and a dorsoventral height that are more or less constant until the distal expansion. The minimum anteroposterior width of the shaft is 28 mm, and occurs about 33 mm distal to the proximal end of the femur. The minimum height of the shaft is 13 mm, and occurs approximately at the mid-length of the femur. The dorsoventral height of the distal end is 65 mm, and in this region the dorsoventral height is 18 mm. For the complete list of measurements see SOM 2: table S3.

The proximal articular head is strongly dorsoventrally expanded and slightly anteroposteriorly expanded. This articular end is composed of the capitulum and the trochanter. There is no well-developed or distinct separation between the capitulum and the trochanter. This feature, along with other previously mentioned characters related to the pubis and vertebrae, indicate that the specimen could be a young adult. The capitulum consists of a large hemispherical, convex, and pitted articulation that covers most of the proximal and ventral surfaces of the proximal end of the femur. Along the posterodorsal surface, the capitulum is separated from the trochanter by a concave depression. The dorsal trochanter exhibits as an elevation that begins and rises at the dorsal surface of the shaft until it reaches its maximum elevation at the articular proximal end of the femur. The articular surface of the trochanter is located more distally than that of the capitulum and is half its width. This surface is slightly concave, rugose and subcircular in outline. The entire surface of the shaft surrounding the proximal articular end is covered by small, irregular and proximodistally-oriented striae. Although the femur is a fairly symmetrical bone, in dorsoventral view, the posterior margin is slightly more curved and proximodistally concave due to the posterior expansion of the capitulum. In contrast, the anterior margin remains straight until the expansion of the distal end of the femur begins. The shaft (without counting the proximal and distal expansions) is straight, dorsoventrally compressed, with nearly-parallel margins, and elliptical in cross-section. Most of the surface of the shaft is smooth, however, on the proximal half of the ventral side there is a surface roughness corresponding to the adductor musculature insertions. Within this course region is a protuberance that connects with an irregular ridge, which is directed proximodistally. This ridge may correspond with the trochanteric crest, which marks the insertion of the M. puboischiofemoralis externus (Bardet et al. 1999b). Posterior to the crest, on the ventral surface, there is an associated depression. In dorsoventral view, the shaft of the femur flares distally in a fan-shaped anteroposterior expansion. Although this flared distal portion is quite symmetrical, the posterior expansion is slightly larger. This portion of the femur is also covered with fan-like longitudinal striations for muscle attachment. The flared distal end bears the tibial and fibular facets, although the boundary between them is not clear. The articular distal end is rugose and lenticular in cross-section.

Phalanges: Only two phalanges are associated with ML2302. The larger phalanx is derived from a more proximal position on the paddle, while the smaller phalange is from a more distal position. Little distortion or weathering is apparent on either element. The larger phalanx (Fig. 4D) measures 27 mm proximodistally, the width (measured along the anteroposterior axes on the articular facets of the phalanges) of the proximal end is 14 mm, and the width of the distal end is 11 mm. The smaller phalanx measures 25 mm proximodistally, with a width of 11 mm along the proximal facet and 11 mm for the distal facet. The phalanges are dorsoventrally compressed and constricted along the shaft. The distal ends of both are flatter, while the proximal ends are convex. No striae are apparent on the surface of the phalanges. The distal and proximal facets are rugose.

Remarks.—The 17 dorsal vertebrae span the mostly complete dorsal series and provide data on the morphological changes of the dorsal vertebrae along the vertebral column. The fully fused neural arches on the centra, as well as the articular facets on the humerus, femur, ischium, and pubis suggest a sub-adult to adult life stage for ML2302 (e.g., Brown 1981).

Geographic and stratigraphic range.—Type locality and horizon only.

Phylogenetic analysis

For cladistic analysis, the plesiosaur Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. was scored and added to the matrix of Madzia and Cau (2020) since it is one of the most recent and updated matrices, and with the highest number of taxa. This matrix is in turn a modification of previous works such as Benson and Druckenmiller (2014), Fischer et al. (2017), Serratos et al. (2017), Madzia et al. (2019), and Sachs et al. (2020). With the new taxon, the dataset included 126 taxa, which were coded for a total of 270 craniodental and postcranial characters. Neusticosaurus pusillus (Fraas, 1881) was used as the outgroup taxon. All characters were equally weighted and some multistate characters were ordered (additive) as in Madzia et al. (2019). The parsimony analysis was performed with TNT v.1.5 (Goloboff and Catalano 2016). The TNT file of the matrix is available in the SOM 3. The memory of TNT was set to 950 000 trees, the maximum amount that the computer memory allowed.

A first analysis was performed using a heuristic search algorithm (traditional search method), with tree-bisection-reconnection (TBR) branch swapping, random seed set to 1 and 1000 random addition replicates holding 10 most parsimonious trees for each replicate. To recover all trees, a second search using the not overflowed trees retained in the memory was performed.

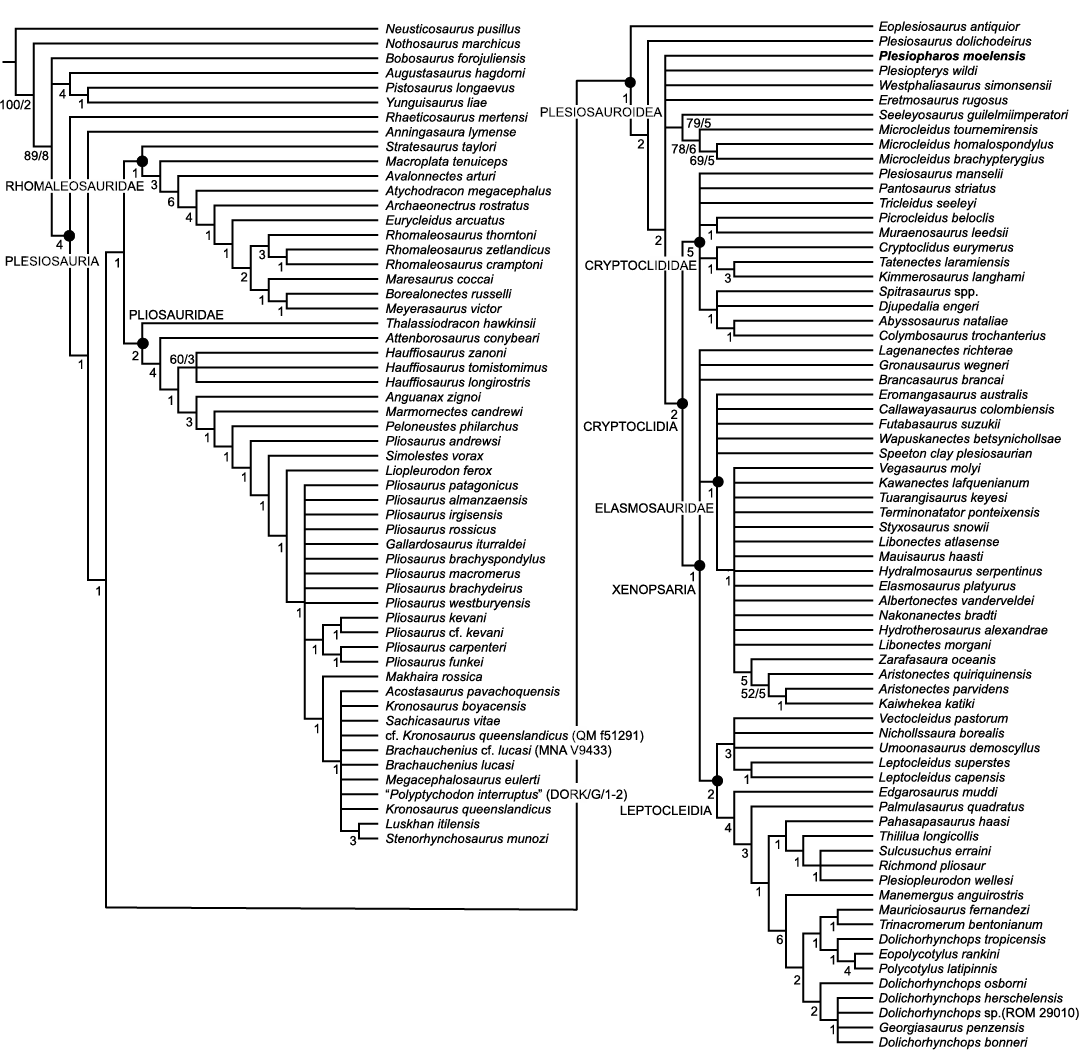

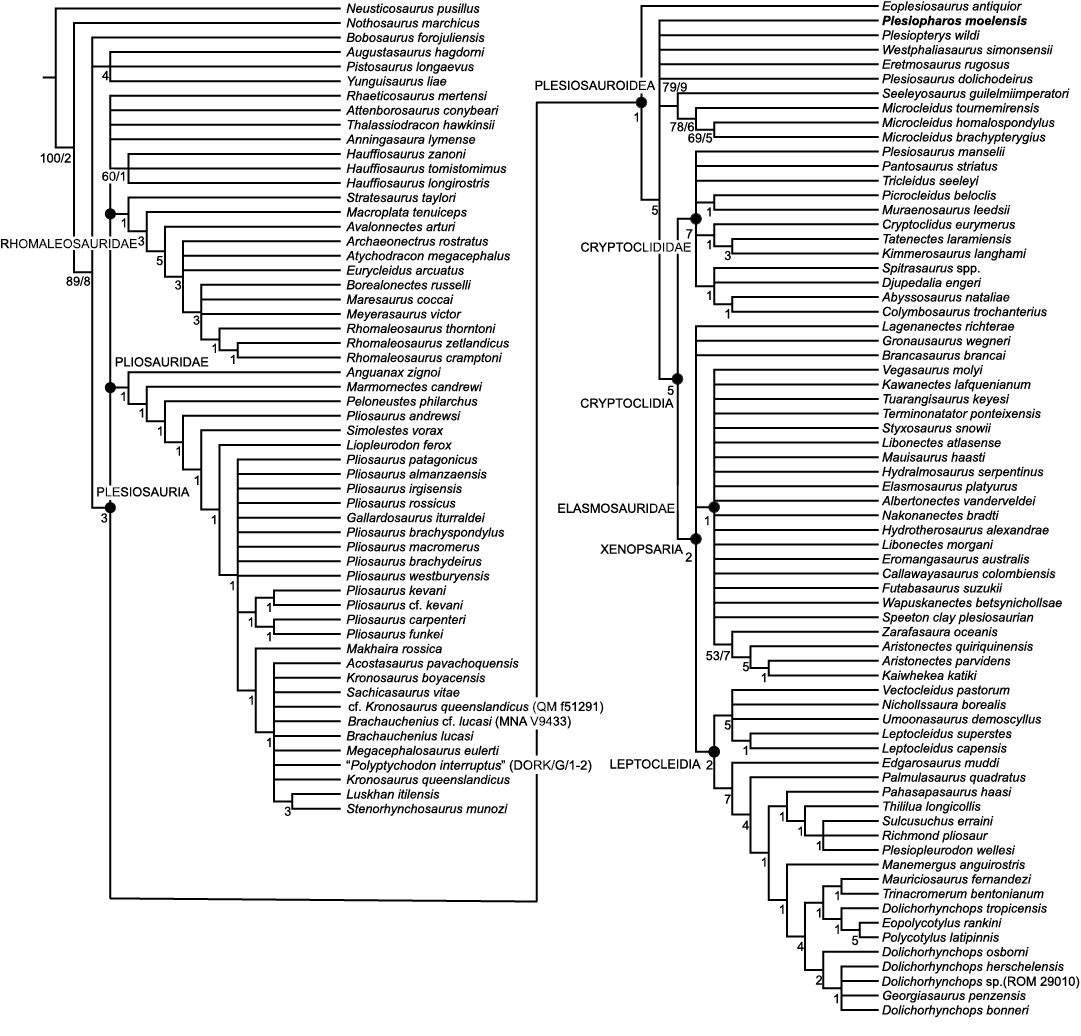

The traditional search returned 950 000 most parsimonious trees (MPTs) of 1971 steps (ensemble consistency index, CI = 0.202; ensemble retention index, RI = 0.695; rescaled consistency index, RC = 0.141). The bootstrap frequencies and the Bremer support (decay index) were summarized in the strict consensus tree (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Phylogenetic relationships of Plesiosauria by traditional search method in TNT, depicting the position of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. (ML2302) based on the matrix of Madzia and Cau (2020). Strict consensus tree of 950 000 most parsimonious cladograms with 1971 evolutionary steps. Numbers of each node indicate the Bremer support and the bootstrap frequencies over 50%.

Since we were unable to complete the analysis, as the maximum number of trees allowed by the ram was reached (950 000) and we could not be exploring all global optima (“islands”), we decided to perform a second analysis with “New Technology Search”. This type of analysis is recommended for large and very complex data sets as it includes algorithms that are much more effective than simple branch-swapping. The matrix was analysed using driven search with 5 times of “Stabilize consensus” option in the “New Technology Search” and random seed = 1. The analysis was combined with “Sectorial search” (100 drifting cycles), “Ratchet” (100 iterations), “Drift” (100 cycles) and “Tree fusing”. The rest of the analysis settings were left by default. After this first analysis, we performed “Traditional Search” through the tree bisection and reconnection (TBR) branch swapping with the previously obtained trees (trees from RAM) to explore the tree islands inferred by the first round of “New Technology Search”.

The “New Technology Search” returned 237 most parsimonious trees (MPTs) of 1971 steps (ensemble consistency index, CI = 0.202; ensemble retention index, RI = 0.695; rescaled consistency index, RC = 0.141). The bootstrap frequencies and the Bremer support (decay index) were summarized in the strict consensus tree (Fig. 6). The traditional search from the trees stored in the ram was completed until the buffer is filled (950,000 most parsimonious trees recovered), and the steps, strict consensus tree topology, index, Bremer and bootstrap supports were the same as the ones obtained with the first round of “New Technology Search”.

The results and tree topology obtained are difficult to compare with the study where the original matrix comes from (Madzia and Cau 2020). This is due to these authors not performing a parsimony analysis to explore the matrix, as they based their work on Bayesian analyses to estimate the rates of divergence of clades, an objective outside the scope of the present work, which is more interested in the phylogenetic position of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. Nevertheless, one of the main differences observed from the Bayesian analysis of Madzia and Cau (2020) is that they obtained Rhomaleosauridae as the sister clade of Neoplesiosauria (Pliosauridae + Plesiosauroidea) while our result placed within Neoplesiosauria and sister taxon of Pliosauridae.

Fig. 6. Phylogenetic relationships of Plesiosauria by “New Technology Search” method in TNT, depicting the position of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. (ML2302) based on the matrix of Madzia and Cau (2020). Strict consensus tree of 237 most parsimonious cladograms with 1971 evolutionary steps. Numbers of each node indicate the Bremer support and the bootstrap frequencies over 50%.

The strict consensus tree topologies obtained by “Traditional Search” (Fig. 5) and “New Technology Search” (Fig. 6) were very similar, although the former is better resolved. The main difference between both analyses is that in the traditional search the phylogenetic relationships between the major clades of Plesiosauria are resolved with Rhomaleosauridae as sister clade of Pliosauridae, and both clades together (Pliosauroidea) form the sister clade of Plesiosauroidea. As we already mentioned, in this analysis the clade Neoplesiosauria (Pliosauridae + Plesiosauroidea) (sensu Ketchum and Benson 2010; Benson et al. 2012) is not recovered, in contrast with more recent parsimony analyses (see Madzia and Cau 2020 and references therein). The “New Technology Search” does not resolve these relationships, and the major clades form a polytomy at the base of Plesiosauria along with other taxa such as Rhaeticosaurus, Attenborosaurus, Thalassiodracon, Anningasaura, and Hauffiosaurus. Within the main clades, the topology obtained by both analyses is more similar. Although less resolved, we consider that the analysis obtained through “New Technology Search” is more reliable since it was probably able to explore all global optima, therefore we will use this analysis to explore the phylogenetic relationships of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov.

Within this phylogenetic context, Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. appears in a basal position within the sister clade of Eoplesiosaurus, the latter appearing as the basal-most taxon of Plesiosauroidea. The base of the clade that contains the other plesiosauroids (except for Eoplesiosaurus) is not very resolved with Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. forming a polytomy with Plesiopterys, Westphaliasaurus, Eretmosaurus, Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus, Seeleyosaurus + Microcleidus, and the clade that contains the remaining Plesiosauroidea (Cryptoclidia). Therefore, although in a poorly resolved position and with low supports, parsimony indicates that Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. was probably related to the basal plesiosauroids.

The position of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. is supported by the following unambiguous synapomorphies: straight preaxial margin of the radius (character 256, state 1). In addition it is also supported by the following ambiguous synapomorphies: horizontal orientation of transverse processes in vertebrae from middle dorsal region (character 182, state 0); dorsal blade of the ilium with subequal anteroposterior expansion and confined to dorsal one-third of ilium (character 223, state 1); subcircular cross section of the shaft around mid-length of the ilium (character 226, state 0); not inclined proximal end of the humerus in dorsal view, which extends proximally so the shaft appears straight (character 249, state 1); anteroposteriorly long shallow groove between the epipodial facets on the ventral surface of the humerus (character 250, state 0).

Discussion

The position of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. within Plesiosauria is supported by various characters. Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. shares with all plesiosaurs the presence of zygapophyses facing dorsomedially, in contrast with some pliosaurids and non-plesiosaur sauropterygians such as Bobosaurus, Nothosaurus, or Yunguisaurus, whose zygapophyses are horizontally oriented. Also, the occurrence of subcentral foramina on the vertebral centra is a plesiosaurian synapomorphy, not present in the aforementioned non-plesiosaur taxa (Brown 1981; O’Keefe 2001; Bardet et al. 2008a; Wintrich et al. 2017b). Another character present in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. and common to all plesiosaurs is the presence of a shorter radius in contrast to the longer radius present in other sauropterygians such as nothosaurs and non-plesiosaur pistosaurians such as Augustasaurus, Pistosaurus, or Yunguisaurus (e.g., Sues 1987; Ji et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2020). In Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. there is a lack of contact between the ilium and the pubis, a character traditionally considered as a synapomorphy of Plesiosauria (e.g., Andrews 1910; Druckenmiller and Russell 2008; Bardet et al. 2018); however a few Triassic pistosaurians such as Bobosaurus and Yunguisaurus also lack this contact (Dalla Vecchia 2006; Sato et al. 2010; Benson et al. 2015a). Other features related to the pelvic girdle, such as the presence of a large pubo-ischiatic plate also indicate a plesiosaurian affinity of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. (e.g., O’Keefe 2001; Druckenmiller and Russell 2008; Bardet et al. 2018). In addition, the presence of a median pelvic bar between the pubis and the ischium, is considered as a plesiomorphic character for plesiosaurs (Druckenmiller and Russell 2008; Bardet et al. 2018).

The position of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. within Plesiosauroidea is also supported by several synapomorphies that differentiate it from other clades such as Pliosauridae. For example, length/width proportions of the ischium have been considered, generally, a distinctive character between Plesiosauroidea (shorter ischium) and Pliosauridae (longer ischium) (e.g., Welles 1943; Brown 1981; Bardet et al. 2018). The case of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov., with an ischium approximately as wide as it is long (length/width ratio ≈ 1), is more similar to the condition observed in Plesiosauroidea and Rhomaleosauridae. In contrast, in pliosaurids this ratio is usually around 2. The morphology and general outline of the ischium is almost identical to that observed in rhomaleosaurids such as Eurycleidus (Smith 2007) or the Microcleididae Microcleidus (= Occitanosaurus) tournemirensis (Bardet et al. 1999b), although the anteromedial process and the medial blade of the ischium are somewhat more rounded in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov.

The presence of a pubis almost as wide as it is long is also different from the pliosaurids and more derived polycotylidids that usually have pubis that are longer than in the rest of the plesiosaurs (see the distribution of character 229 relative to the proportions of the pubis through Plesiosauria). The shape and general contour of the pubis is also almost identical to that seen in Eurycleidus (Smith 2007), with a pubis exhibiting a notch on its anterior margin dividing two rounded lobes and without cornu on its lateral margin. However, the anteromedial lobe and acetabular facet are more developed in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. By contrast, the posteromedial process of the pubis is lateromedially wider in Eurycleidus (Smith 2007), indicating a more developed pelvic bar. Although both the pubis and the ischium of Eurycleidus are very similar to those observed in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov., other elements such as the ilium or radius are clearly different and indicate that they are different taxa.

The propodial proportions of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. are also more similar to those present in Plesiosauroidea and Rhomaleosauridae than in Pliosauridae. The presence of a robust humerus (length/width = 2) in ML2302 is typical of most plesiosauroids and rhomaleosaurids. By contrast, non-thalassophoneans pliosaurids present more slender humeri (length/width between 2.3 and 2.7) (Benson and Druckenmiller 2014; Páramo-Fonseca et al. 2018). Comparing with other plesiosauroids, the robustness of the humerus of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. is also different from that observed in most elasmosaurids, which is generally even higher (length/width <1.6) (Welles 1943; O’Keefe 2001; O’Gorman et al. 2015). Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. has a humerus with a sub-equal length to the femur, and on the contrary, the humerus is shorter than the femur in most thalassophoneans pliosaurids (e.g., Tarlo 1960; Benson and Druckenmiller 2014; Fischer et al. 2017; Páramo-Fonseca et al. 2018). As in most plesiosaurs, the distal articulation of the propodials of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. is smooth, in contrast with the complex multifaceted tongue-and-groove articulation observed in Polycotylidae (e.g., O’Keefe 2004a; Schumacher and Martin 2016). In dorsoventral view, this distal margin is uniformly convex, a character shared with rhomaleosaurids, basal pliosaurids and some basal plesiosauroids such as Eoplesiosaurus, Westphaliasaurus, and Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus (e.g., O’Keefe 2001; Benson et al. 2012). One of the characters that Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. shares with basal plesiosauroids such as Eretmosaurus and Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus, but also with a few basal rhomaleosaurids and basal pliosaurids such as Eurycleidus and Thalassiodracon, is the presence of an anteroposteriorly long shallow depression on the ventral surface of the humerus between the epipodial facets. In the rest of Plesiosauria this depression or groove is very short or non-existent.

One of the characters that differentiates Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. from basal plesiosauroids and rhomaleosaurids, but is present in most of Pliosauridae and derived Plesiosauroids (Cryptoclidia), is the presence of a straight (not concave) preaxial margin of the radius. However, the radius is much more slender than that observed in Cryptoclidia and Pliosauridae, having more similar dimensions to those of rhomaleosaurids and basal plesiosauroids. Also, the absence of a posterodistal facet for the intermedium observed in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. is also common in basal plesiosauroids and some rhomaleosaurids. A character that differentiates Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. from Rhomaleosauridae and some basal plesiosauroids such as Westphaliasaurus, Eretmosaurus, and Microcleidus, is the absence of a prominent anterior flange on the radius.

Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. has posterior cervical vertebrae with two co-joined rib facets that differentiate it from most plesiosauroids with the exception of some basal taxa such as Plesiopterys. This character, however, is present in rhomaleosaurids and some basal pliosaurids such as Pliosaurus andrewsi Tarlo, 1960. The presence of sub-cylindrical vertebral centra allows Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. to be differentiated from other plesiosauroids such as Elasmosauridae, whose cervical centra are usually “binocular” shaped. The presence of convex and poorly expanded apices on the spines of the posterior cervical and anterior dorsal vertebrae in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. is common in most plesiosauroids, with the exception of Polycotylidae, and also differentiates it from pliosaurids and most rhomaleosaurids, where these apices are transversely expanded. In Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov., the rest of Plesiosauroidea and most rhomaleosaurids, the dorsal transverse processes are composed of a single subcircular facet, which contrasts with the condition observed in pliosaurids, whose processes are composed of two weakly divided rib facets. Also, in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov., the laterally-oriented transverse processes of the medial dorsal vertebrae are more similar to those observed in most rhomaleosaurids and differ from most pliosaurids and plesiosauroids, whose processes are dorsolaterally oriented. The neurocentral sutures of the last cervical and first pectoral vertebrae are v-shaped with a dorsoventral ridge between the tip of the suture and the rib facet. This condition has been observed in plesiosaurs such as “Plesiosaurus” cliduchus Seeley, 1865, basal plesiosauroids such as Plesiopterys, basal pliosaurids such as Arminisaurus and rhomaleosaurids such as Avalonnectes and Eurycleidus (e.g., O’Keefe 2004b; Benson et al. 2012; Sachs and Kear 2018). Also, the inclined apex of the neural spine of the first pectoral vertebra is very similar to that of “Plesiosaurus” cliduchus (Seeley, 1865), although in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. the tip of the posterior margin of the spine forms a more individualized, convex and rounded tip than in “Plesiosaurus” cliduchus.

The ilium of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. is probably the most distinctive and diagnostic bone. The overall ilium proportions are similar to those of the basal plesiosauroids, in contrast with that observed in other clades such as Pliosauridae and Rhomaleosauridae, whose majority of representatives have wider and more robust ilia. The general morphology of the ilium of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. is reminiscent of that of microclidids, cryptoclidids such as Cryptocleidus and Muraenosaurus (O’Keefe et al. 2011), rhomaleosaurids such as Stratesaurus (Benson et al. 2015a, b) or the plesiosaur “Raptocleidus” (nomen nudum, Evans 2012), although several differences allow ML2302 to be distinguished from all of these taxa.

The expansion of the proximal region and the straight shaft of the ilium in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. is similar to that observed in most plesiosaurs, with the exception of more derived plesiosauroids (Cryptoclidia) whose expansion is asymmetric, with a more curved shaft. The morphology of the proximal region is very similar to that observed in rhomaleosaurids, microclidids and basal pliosaurids (Bardet et al. 1999b; Vincent 2011; Benson et al. 2015a, b), however the ischial facet is more developed in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. In these clades, the ischial facet faces posteroventrally as in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov., however, in thalassophonean pliosaurids, cryptoclidids and xenopsarians this facet faces ventromedially (Benson et al. 2015b). The acetabular facet is oriented differently than some rhomaleosaurids such as Stratesaurus, and is more similar to the rhomaleosaurids described by Benson et al. (2015b). This facet is facing more ventrally and more transversal to the shaft in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov., while in Stratesaurus it is facing more anteriorly and oblique to the shaft.

The most notable differences between Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. and these taxa relate to the orientation and shape of the iliac blade. For example, in early rhomaleosaurids, such as Stratesaurus and Eurycleidus, and basal pliosaurids such as Thalassiodracon, this blade is more equally expanded anteroposteriorly (Benson et al. 2015a, b). On the contrary, in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov., some rhomaleosaurids such as Rhomaleosaurus, cryptoclidids, early pliosaurids such as Hauffiosaurus, and some thalassophonean pliosaurids, this expansion is minor and slightly asymmetric (O’Keefe et al. 2011; Smith and Benson 2014; Benson et al. 2015b). The condition of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. also differs from the extremely asymmetrical blades observed in more derived pliosaurids (Benson et al. 2015b). Regarding the rotation of the iliac blade with respect to the proximal region, Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp.nov. has an oblique rotation of about 45°. A similar rotation can be observed in basal plesiosauroids and rhomaleosaurids. However, this rotation is less developed in some rhomaleosaurids such as Stratesaurus (Benson et al. 2015a, b). In contrast, Pliosauridae and Cryptoclidia usually have almost perpendicular rotations close to 90°.

The morphology of the iliac blade in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. is different from that observed in most plesiosaurs. In plesiosaurs with an expanded iliac blade, the anterior and posterior expansions usually have concave or straight outlines (e.g., Stratesaurus, M. tournemirensis, Eurycleidus, Cryptocleidus, and Muraenosaurus). On the contrary, the anterior expansion in Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. has a convex and rounded outline. A similar iliac blade contour has been observed in some rhomaleosaurids (Benson et al. 2015b), however, the orientation, development and torsion of the proximal iliac region are different in these taxa. The shaft of the ilium of Plesiopharos moelensis gen. et sp. nov. is subcircular, unlike basal plesiosauroids, pliosaurids and rhomaleosaurids, and more similar to that observed in Cryptoclididae and Elasmosauridae.